Célia Belin

Head of @ECFRParis and @ecfr. Senior Policy Fellow. Non-Resident Fellow @BrookingsFP. Author "Des démocrates en Amérique" (Fayard 2020)

In the first year of the war in Ukraine, Europeans could count on a US administration that facilitated transatlantic solidarity and unity. This may have added to the impression that only the return of Donald Trump, or some other Trumpian Republican, in 2025 could really jeopardise European-US relations. However, deep foreign policy debates are brewing within the Democratic camp too. Even if these are often less noticeable, such debates increasingly constrain President Joe Biden’s capacity to support Ukraine, and will force choices on budget and policy ahead of the election next year and beyond.

Célia Belin, Head of the European Council of Foreign Relations @ECFRParis

Originally published on the ECFR website, EFCR.eu

What Unites Democrats

Foreign policy divisions among Democrats are less stark than those tearing apart Republicans because of the Democrats’ political imperative to support the president. At a time of high polarisation, intra-party controversy is less tolerated. When a group of 30 progressive lawmakers published a letter to Biden urging talks to end the war in Ukraine in October 2022, the letter was retracted within three days. As Biden will soon launch into re-election mode, Democrats’ strategy is to trumpet the successes of the president’s first two years – including standing up to Vladimir Putin and passing ambitious legislation on climate and infrastructure to “build back better” – not to indulge in divisions.

This unity strategy is all the more effective because Democrats are mostly united on numerous issues.

Firstly, Democratic lawmakers have rallied behind the president to support Ukraine and push back on Russia’s aggression. As an anti-Ukraine discourse is starting to emerge on the far-right of the Republican camp, Democrats underline that they stand with Ukraine. Secondly, with the 20-year “war on terror” drawing to a close, a strong sentiment against military intervention is still prevalent, with little to no appetite for conducting operations in the Middle East, the Gulf, or Africa. Meanwhile, the administration’s focus on Asia – and China – is widely supported by Democrats. Thirdly, the administration’s climate change and industrial policies have generated wide support – they sit at the intersection of domestic and foreign policy and are a visible application of the administration’s “foreign policy for the middle class”. While transregional trade partnerships, such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership are now unpopular, the Inflation Reduction Act and Chips Act received unanimous support among Democrats in Congress.

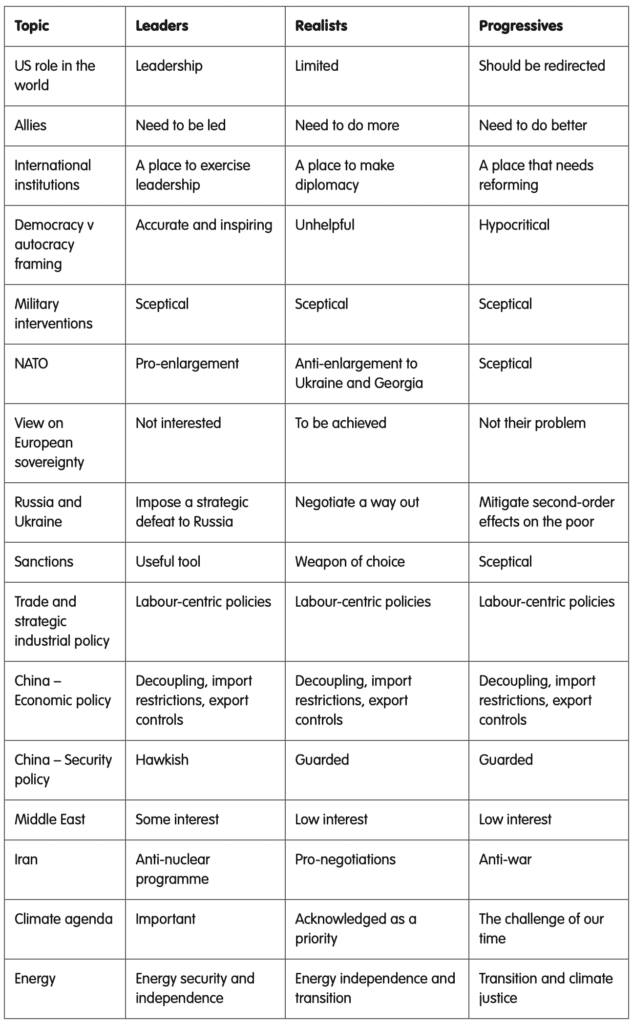

Defining the tribes

Despite broad agreement on issues such as Ukraine, climate change, and industrial policy, increasingly visible foreign policy divisions are emerging among Democrats. These are unlikely to surface soon because of next year’s presidential election, but they will profoundly shape the orientation of the administration, and the next, if it is Democratic. Three “tribes” represent broad groupings of lawmakers and experts who rally around certain instincts and approaches.

The leadership tribe

A substantial portion of the Democratic party, inheritors of the cold war internationalism tradition, continues to believe in America’s role as a guarantor of world order. They believe that the United States must assume a leadership position, stay focused on its alliances, and push back against revisionist powers, Russia and China first and foremost. Along with Biden, this tribe includes individuals such as Senator Bob Menendez, chair of the foreign relations committee, Senator Dick Durbin, chair of the Senate Ukraine Caucus, and former intelligence officer Congresswoman Elissa Slotkin, who calls herself a “believer in a strong American leadership in the world”. These “leaders” express strong support for NATO, including sending tanks, along with Germany, to keep the alliance strong, and they back Finnish and Swedish NATO membership. They are also highly focused on building up Asian alliances: the Quad, AUKUS, US-Japan-ROK, and US-ASEAN are all now cornerstones of American strategy in Asia.

On Ukraine, “leaders” are focused on imposing a strategic defeat on Russia, for which, in the words of Congressman Seth Moulton, “any weapon should get to Ukraine; there is no negotiating with Putin; he must be stopped or another NATO country is at risk”. The same goes for China: the leadership tribe encourages the administration to do more in Ukraine in order to send a message to China. Senator Menendez advocated “clarity in word and deed” on Taiwan after Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to the island, in contrast with the decades-long US policy of strategic ambiguity on Taiwan.

The realist tribe

As the war in Ukraine has reinforced the leadership tribe, a more “realist” tribe has emerged. This loose tribe is more prevalent in think-tanks than in Congress. Its members believe American power is limited, that the international system is moving inexorably towards multipolarity, and that the US should focus primarily on vital interests while leaving allies and partners to take up more of the slack.

“Realists” are wary of military entanglements and viewed the Afghanistan withdrawal as a necessary, long-overdue decision. Senator Chris Murphy, a member of the US senate foreign relations committee, has spoken in favour of sunsetting future authorisations for use of military force after two years, in order to place a check on the interventionism of the executive branch. “Realists” pay close attention to military strategies that may drag the US into future conflicts and they denounce rhetoric that, in their view, increases the risk of US-China conflict over Taiwan. For Senator Brian Schatz, who voted against legislation intended to boost Taiwan military defences, these efforts offer Taiwan “symbols of sovereignty” that “may irritate the Chinese”.

On Ukraine, “realists” are focused on finding an exit. They are ready to support negotiations when conditions are appropriate, even if Ukraine may have to make territorial concessions – ultimately, they believe that Russia will have learned its lesson by paying a price for these concessions. Realist think-tank experts have made the case for caution and diplomacy and warned of the risk of a long war.

“Realists” advocate the use of sanctions, or even economic warfare, as elements of integrated deterrence, but also anti-corruption and anti-kleptocracy legislation as ways to sap the strength of authoritarian powers. They believe in the rules-based order as a means to constrain actors and build global consensus. Similarly, climate-friendly policies are to be put to use in constraining revisionist power. As Senator Ed Markey puts it, “we can destroy the business model of Russia and of Saudi Arabia if the West goes to all-electric vehicles”.

“Realists” are often critical of Europeans for not doing more in response to Russia’s war on Ukraine. In October 2022, Senator Murphy criticised Europeans for their overreliance on Russian energy and encouraged them to do more to diversify their sources. In turn, “realists” are ready to accept a certain level of strategic autonomy on the part of Europe, as long as it allows for better burden-sharing.

The progressive tribe

In contrast to the leadership tribe, “progressives” believe that American power is too militaristic, supports oppressive regimes, and has to be redirected. With deep roots in the Congressional Black Caucus and in trades union activism, “progressives” care about social and racial justice and advancing the working class. In domestic as in foreign policy, “progressives” are pro-poor, pro-minorities, pro-immigrant, pro-LGTBQ, and pro-worker. For many of them, such as Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the US should lead a climate-based foreign policy, one that would tackle climate change as a source of poverty and migration in the global south. Others, such as Congressman Ro Khanna, believe the US should seek to become once again a global manufacturing superpower.

“Progressives” are committed to the defence of Ukraine, which they view as the victim of a war of aggression. They voted largely in favour of economic assistance, although several of them opposed increased military aid. In the long term, “progressives” worry about nuclear escalation and the use of offensive weapons. They lament the over-militarisation of foreign policy in general, and worry that the US is pushing to a military build-up in Asia through AUKUS and other military agreements. A small group of members of Congress, called the Defense Spending Reduction Caucus, are pressing for a reduction in the military budget, and for some of this to be redirected towards social programmes at home. In early 2023, the caucus’s co-chairs, Representatives Barbara Lee and Mark Pocan, pleaded for $100 billion of the Pentagon’s budget to be slashed.

“Progressives” believe the US should stop supporting corrupt allies, such as Saudi Arabia, for the sake of security. It should instead tackle transnational threats such as global hunger, transnational crime, and climate change. They criticise the use of sanctions because of the risk they pose to poor and vulnerable populations, including sanctions against Russian oil in the case of Congresswoman Ilhan Omar.

The Democrats’ three foreign policy tribes

Challenges for Europe

For Europeans, each tribe brings its own set of challenges. The leadership tribe provides comfort in its strong support for NATO – but its members have little patience for European strategic autonomy and want Europeans to align with the US on dealing with China. The realists tribe may grow impatient with the enduring conflict in Europe, and push for a reduced American presence there. They would rather see the administration focus on a few core interests and are reluctant for the US to lead the Western camp. The progressives are highly sceptical of US military engagement in the world and would rather focus on transnational threats. They increasingly expect rich European countries to foot the bill for the war in Ukraine and its reconstruction, and advocate diversifying partnerships towards non-Western countries.

Europeans should stay mindful of the challenges ahead for their relationship with the Democratic administration. Transatlantic solidarity over Ukraine increasingly coexists with transatlantic tensions on other matters, including industrial policy and China strategy. After a year of renewed US leadership under the duress of the war, the Biden administration will rebalance towards realist and progressive positions as it prepares for re-election. Europeans should take this as an opportunity to engage the administration on shaping a sustainable transatlantic relationship.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.